The Path Not Taken: Reconsidering the Way of Winthrop

The article is the second in a series of responses to Episode 2.4 of the Genealogies of Modernity podcast.

On January 11, 1989, President Reagan delivered his farewell address. In his speech, the Gipper framed himself as an unlikely politician who was no more than a reluctant citizen magistrate who felt obligated to restrain government overreach and let Americans—and America by extension—recover their liberty and, thus, their lost greatness. Reagan was not only a master of crafting his public persona, but also that of the American people. What “folks” in the ‘80s were calling the “Reagan Revolution,” he claimed, was nothing more than the “rediscovery of [American] values and common sense” that emerged “from the heart of a great nation.” To be sure, one of Reagan’s most enduring—and to some, endearing—characteristics was his almost unshakable belief in the exceptionalism of the United States of America. This exceptionalism intimately wove itself into a vision of Americans as self-sufficient, independent, and free from government authority and obligations to the commons.

I was reminded of Reagan and his farewell address as I listened to Caro Pirri and Ryan McDermott unpack the ways in which the Jamestown Colony propagated the myth of the sovereign family. Pirri notes that the “idea of the American family as insular and self-sufficient shows up all over [the American] cultural imaginary” and goes back to the early frontier days. From Laura Ingalls to the libertarian Koch brothers to op-eds in The Wall Street Journal asking Obama to leave middle-class families alone, this enduring narrative of a family freed from the expansive state has had a powerful hold on the American psyche as it defines its “greatness.”

Ronald Reagan with Barry Goldwater, 1964

What compels me about Reagan’s vision of America is that it was summed up in his economic vision, coined as Reagonomics. This was a program that slashed taxes for the wealthy, cut government programs, and framed Americans as one of two types: hard-working producers or lazy consumers who, at their worst, waited for some government handout rather than lift themselves up through sheer effort and determination. It’s not hard to see how such a vision championed individuals and nuclear families to put their economic self-interest first and to see government as nothing more than a bureaucratic impediment to individual and familial freedom. Even worse, the poor were not imagined as members of a shared commons to whom charity—in every sense of that word—was owed, but as leeches who threatened the self-sufficiency, wealth, security, and greatness of America.

According to Lou Cannon, in an article published in The Washington Post shortly after Reagan’s departure, Reagan’s individualistic vision was rooted in a particular telling of American history which was as inspiring to Reagan as it was inaccurate:

[Reagan] imagined that the American nation had been carved from wilderness by pioneers unrestrained by the forces of nature or the power of state. The tales he loved most as boy and man were stories of individualist heroes. Reagan never noticed that it was the government that had protected these frontier heroes, set aside land for homes and schools, built telegraph lines and underwritten construction of an intercontinental railway system. The individualist myths that formed the core of the Reagan vision ignored government’s role in the building of the West, as Reagan ignored the beneficial role of the federal government in his own life.

Reagan was concerned that some tellers of America’s history—some keepers of the family genealogy—might not tell the stories quite right. That is, they might not see in America’s past the ineluctable march to greatness and liberty that he always envisioned out his Oval Office window. “I’m warning of an eradication of the American memory,” Reagan intoned in his farewell address, “that could result, ultimately, in an erosion of the American spirit.” Yet significantly and, it turns out, ironically, in Reagan’s own version of America’s family history, he makes a pointed allusion to John Winthrop’s famous sermon “A Model of Christian Charity,” enlisting the Puritan settler’s sermon in ways that could not be further from what Winthrop actually intended.

As he concluded his talk, Reagan became reflective and expansive: “The past few days when I’ve been at that window upstairs, I’ve thought a bit of the ‘shining city upon a hill.’ The phrase comes from John Winthrop, who wrote it to describe the America he imagined. What he imagined was important because he was an early Pilgrim, an early freedom man.” Winthrop was a Puritan and not a Pilgrim or “freedom man” as Reagan claims. The Pilgrims had come over in the 1620s via the Mayflower, many of whom were seeking separation from the Church of England for a host of reasons. They were often poor and disorganized, and there were fewer of them than later migration movements. Many who settled in and around Plymouth did so without any real support from the Old World. John Winthrop, unlike the Pilgrim leader William Bradford, was educated as a lawyer, came to the New World with a sizable endowment, had a large community of Puritans (almost 700), and came with the backing of the king—that is, government authority—to claim territory in Massachusetts.

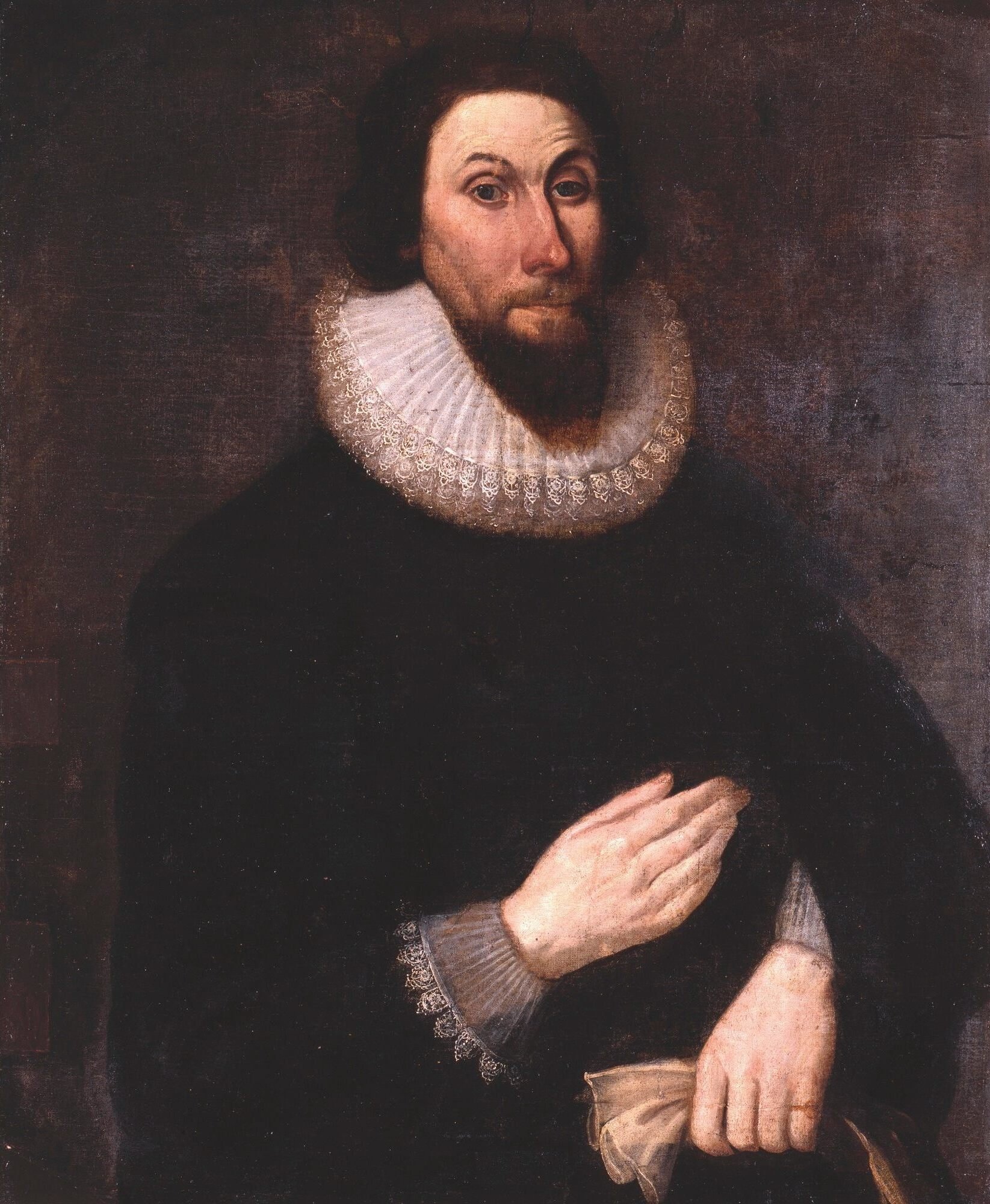

John Winthrop, (1600s)

Reagan’s subtle “slip” on Winthrop as an early Pilgrim rather than a Puritan is telling. It subtly, but significantly, rewrites the genealogy and conflates the Pilgrims and Puritans in a way that ignores complexity in the hopes of a clear and monolithic American origin story. While Reagan is partly right to characterize Winthrop as a “freedom man” in a boat headed toward America, Winthrop was also someone who was deeply cautious about the colonial enterprise and understood that its authority—however they might begrudge it—derived from the king, and its success would be determined by how individuals understood themselves as indebted to the commons.

What I find so intriguing about the critical genealogy approach is that, to reiterate Ryan McDermott, it interrogates mythical origin stories and then seeks to examine other paths that were not taken. If the Jamestown Colony and its mythic vision of the sovereign family perpetuated a false narrative that carried into Reagan’s imaginings and beyond, it is interesting that another model of social life existed from the earliest days. In fact, this model is encoded in the actual Puritan “sermon” of John Winthrop that Reagan, and so many other champions of American exceptionalism, have (mis)quoted without ever seeming to have read the entire text.

In City on a Hill: A History of American Exceptionalism, literary scholar Abram Van Engen notes that even the phrase “city on a hill” had “almost no relation to the United States until after World War II,” but during the Cold War it became “a shorthand way to assert what America means based in how America began.” But what most forget is that this term used by Winthrop, and taken from the Sermon on the Mount delivered by Jesus in the New Testament (Matthew 5:14–16), had much more to do with discipleship than citizenship. While Reagan fuses Winthrop into his particular American civic religion, he does this in a way that completely goes against Winthrop’s economic and communal vision. John Winthrop was very aware of the struggles of the early Pilgrims and Puritans who had ventured from the Old World to the colonies in the preceding decades. He knew of the hunger winters of Jamestown and, according to Van Engen, was intimately aware that the age-old human vices of self-interest and greed would be the undoing of this congregation who were about to enter into a unique form of communal and civic life together. To counter such vices, they needed to be led by virtue, the chief of which was love—or in the language of the day: charity.

In the full text, Winthrop’s sermon becomes preoccupied, at least for the first half, with debt, finance, and other aspects of economic life. Winthrop goes on at length not only to discern why God allows some to be poor and others rich, but what obligations this puts on every individual to give and receive, lay up treasures in heaven, forgive, and forgive debt. This might sound odd to modern ears, particularly those who imagine a Christian sermon that would spend so much time concerned with economics. But for Winthrop, the reason for this is as clear as it is Calvinist: the world is fundamentally the theater of God’s glory. As such, the diversity of socioeconomic statuses, even within their small community of Puritans on the coast of the New World, was part of God’s providential design in which “every man might have need of others, and from hence they might be all knit more nearly together in the bonds of brotherly affection.” Winthrop’s vision is not of a “sovereign family” but of an interdependent community—weak and vulnerable, yet held together by the bonds of self-giving and sacrificial charity. According to Van Engen, “Talk of debt, loans, and financial exchange in a godly society necessarily leads to a language of love and affection […] As a result, sympathy—defined as the God-given, grace-enabled mutual exchange of love within a godly community—becomes central to Christian Charity.”

There is obviously much more one can, and should, say about Winthrop’s sermon. But at this point it suffices to say that Reagan’s “reading” of Winthrop is strategic and slippery. It uses—rather than listens to—Winthrop’s actual sermon, fitting it within a vision of American exceptionalism that perpetuates the American myth of a self-sufficient, sovereign family that this episode explores. From Reagan’s accounting, American self-sufficiency, wealth, security, and happiness fueled the “beacon” to which the world would turn its eyes. Ironically, it is within that very sermon Reagan misquotes that John Winthrop—completely oblivious to what “America” might become, of course—humbly asked a rag-tag group of Puritans to care for one another, recognize in the New World their deep weakness and vulnerability, and feel keenly the obligation to serve the commons and the larger community, not just their “nuclear” families. He asked them to do so because this is the way of discipleship. This is the way of real, difficult love.

As Winthrop concluded, should they fail in this mission of communal discipleship—that is, should they give in to self-interest, avarice, and the way of vice that is always the unmaking of community—they would have to accept the judgment of the watching eyes of the world. They were witnesses not of American greatness (which would be glaringly anachronistic, to say the least), but of the charity, and the model of Christ, that was at the heart of their Christian faith. If critical genealogy can not only help us better understand where ideas come from, but also reimagine other paths we might have walked, reading Winthrop’s remarkable sermon outside the distorting lens of contemporary American exceptionalism might just help us see that a new way forward—a way of love—is perhaps just a really old way forward. And such a way, as Chesterton once quipped about any Christian ideal, “has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and left untried.”

Doug Sikkema is an assistant professor of English and the Core Program at Redeemer University and an associate editor for Comment magazine. His research area is contemporary American literature with a particular focus on the ways in which the material world is imagined by writers in a postsecular culture. Doug is the board chair of Oak Hill Academy, a classical Christian school located in Ancaster that he helped cofound in 2017. He, his wife, and four children live a good life in the rural environs outside of Hamilton, Ontario.